Extract from the chapter “Challenges of the job search- career history”

From: Making Sense of My Unemployment (M.G. Ramirez-Ocando)

(A list of the interviewees for this extract can be found at the end)

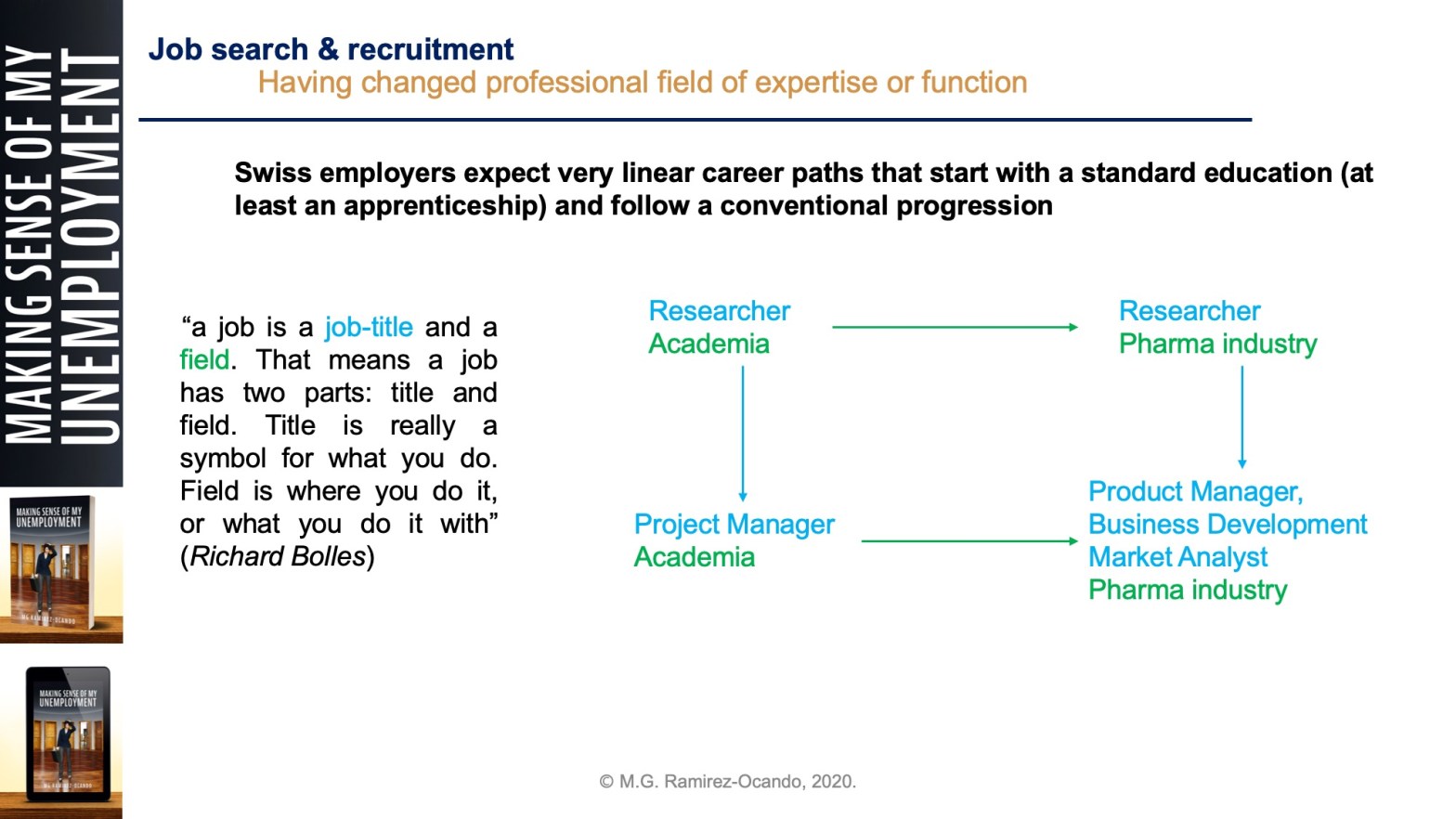

Swiss employers expect very linear career paths that start with a standard education (at least an apprenticeship) and follow a conventional progression. Even though the Swiss education system is permeable (see the section ‘The Swiss education system’ in Chapter 2), it generally frowns upon career changes, in particular when they occur several years after the job seeker’s first career choice. There is an exception, though, and that is when the career change involves moving into a market with high demand (like the case of Weston, who became a primary school teacher in 1972 during a period of high demand for professionals in this area). In general, I would describe the situation as Rose puts it: ‘You have to fit into the Swiss box in order to get hired in Switzerland.’ Given that the majority of the Swiss population choose their career at a very early age, it seems that it is generally expected that people commit to their professional field and/or function for life. For Robert, a Swiss citizen himself, many Swiss employers seem to go as far as to expect that job seekers will have known from a very early age that they want to work for the company they are applying to. Of course, there are some elements of subjectivity in these assessments, but the bottom line is that career changes in Switzerland are frowned upon (unless they are small and gradual or market-driven). This was likely the reason behind the eventual success of Paige’s research–business transition. Like me, Paige used her EMBA as a way to transition from a purely research function to a business-related function in the pharmaceutical industry. Unlike me, however, after her PhD she worked directly in her target industry (pharmaceutical), as a scientist. The change that Paige made was much more gradual: first the industry and then the job type. She also applied for a business post highly relevant to what she did as a scientist (a type of management of preclinical studies). Luke also tried to make a gradual career change, from business analyst to data scientist in the banking industry. His interest in making this change, however, did not survive the first application rejections.

In retrospect, I was probably too bold in making my career change. Maybe I should have first worked as a researcher in the pharmaceutical/biotech industry before seeking a business post in the sector. Maybe I should have worked as a project manager in academia before moving into the pharmaceutical industry. As Richard Bolles wrote in his book:

a job is a job-title and a field. That means a job has two parts: title and field. Title is really a symbol for what you do. Field is where you do it, or what you do it with. A dramatic career change typically involves trying to change both at the same time … The problem with this difficult path is that you can’t claim any prior experience. But if you do it in two steps, ah! That’s different.

Bolles, What color is your parachute?

The two-step process involves changing first the job title or function and then the field or industry, or vice versa. Unfortunately, when I went back to my ‘job title expertise’ and applied for jobs in the research field (including research jobs in academia, research institutions and the pharmaceutical/biotech industry), I was met with a complete brick wall. I applied for several research positions and a couple of positions as project manager that matched my experience very well, but (with two exceptions) I received nothing more than automatic rejection replies. I am not sure what caused this situation. Maybe it was the fact that I had been away from the bench (hands-on work) for more than four years, or maybe I sent the scientific community a mixed message because I had started a career in business. I still have not found the answer to this question.

Changing careers might also have a big impact on the hierarchical level a person ends up at in their next career move. This was one of the things I had to learn to accept. Although I was convinced that the best strategy for entering the new career path was through a business degree and an internship/traineeship (which is the strategy I followed), I was fairly (and mistakenly) confident that I could quickly resume the hierarchical level I had been at on my previous career development path. As a result, for a long time I continued to present myself with the career level I had reached in research (senior specialist/project manager), whereas my career/experience level in relation to the jobs I was applying for was more that of a graduate/entry-level job seeker. I succeeded in being interviewed for a couple of management positions in the pharmaceutical industry, and this gave me the confidence to continue the application processes for these high-level jobs. In the end, however, someone with more years of relevant experience was always chosen. I persisted for a long time in my search for these ‘management’ positions, mainly on the basis that I had highly developed transferable skills and that nobody should be put off by a fancy title. Unfortunately, I ended up losing a lot of time and energy by doing this (within this particular industry sector). By the time I started looking for graduate/entry-level positions within the pharmaceutical industry, too much time had passed since my last graduation (EMBA) and even more time had passed since my first (Master’s in Biology). I managed to get some interviews for these positions, arguing that since I had changed careers, I was technically a young graduate similar to the other candidates in the 22–25 age bracket. Unfortunately, I kept finding myself in a similar dilemma to the one teenagers face when becoming adults: I was too experienced for most entry-level positions and too inexperienced for most other positions. In other words, nobody would let me either play with the kids or have dinner at the table with the adults.

I must admit that for some jobs, the type of studies other candidates had recently finished could be seen as more directly relevant. Then again, it could simply be that employers found it easier to shape new recruits according to their specific tastes and needs when they were fresh out of university. The hiring manager of one of the companies with whom I interviewed did, however, mention that their main concern was that I would get bored quickly and leave. Unfortunately, I was unable to convince the company that this would not be the case; there was very little room for discussion. Rose faced similar challenges during her job search. Given that she was highly specialized in a law field that was not relevant in Switzerland, she was forced to search for positions outside of her area of expertise. After having no luck in her search for management positions, she started looking for junior employment opportunities. Fortunately, in her case, an employer was eventually willing to take the risk of hiring an overqualified candidate because the company had a strong need for lawyers; however, it did take a couple of years to find such an employer.

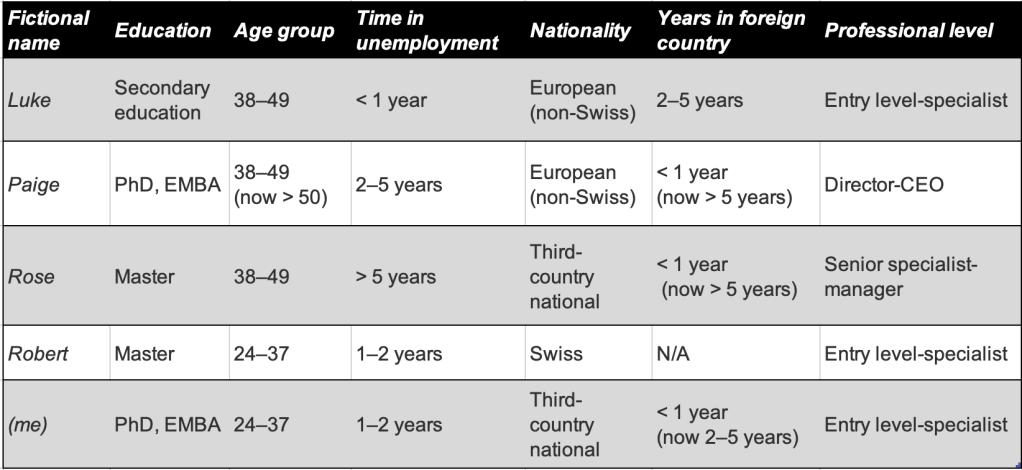

Interviewees for this chapter: