Book available on amazon

Being a Woman

Extract from Chapter 9: Challenges of the job search – identity

From: Making Sense of My Unemployment (M.G. Ramirez-Ocando)

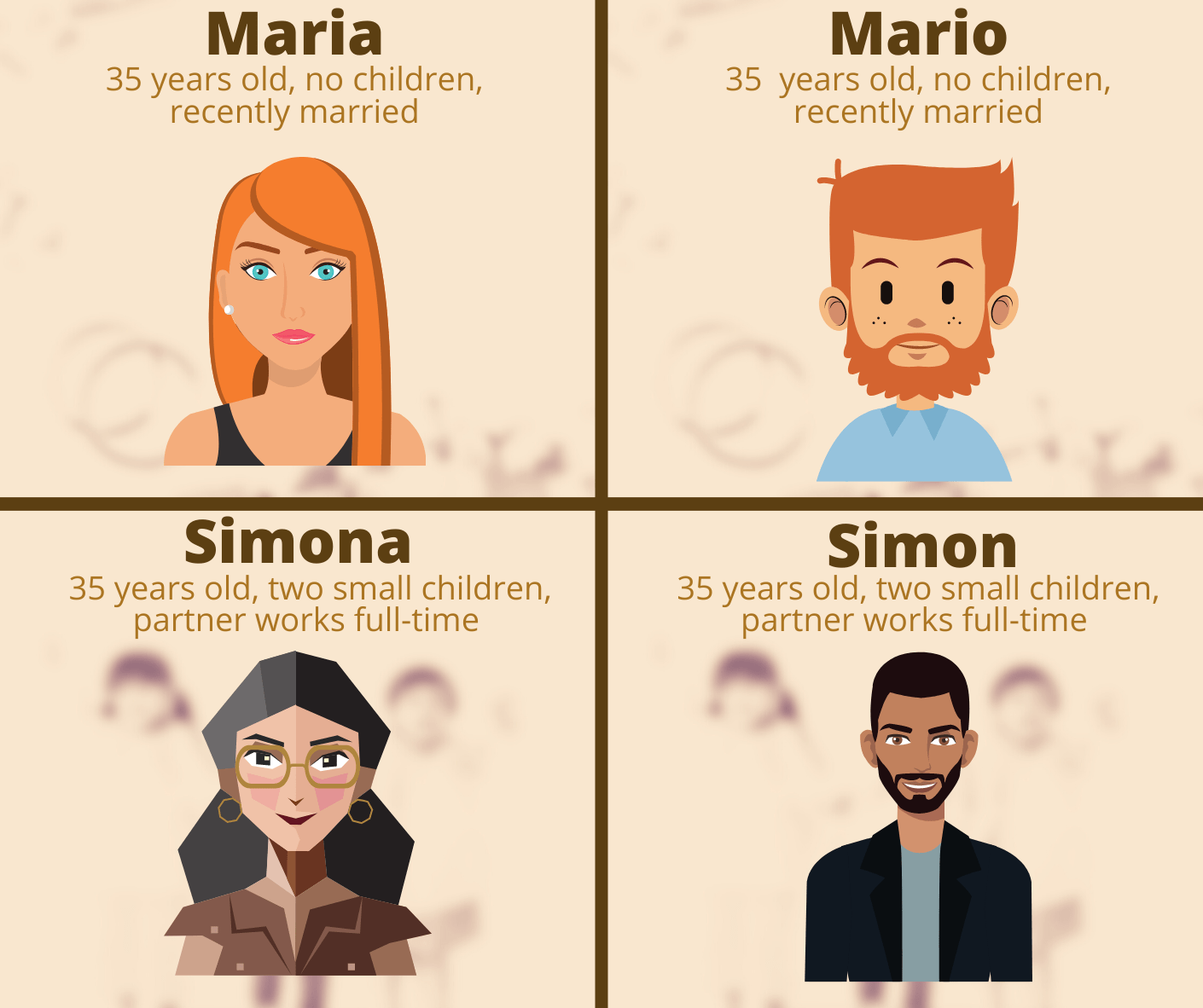

Who would you hire?

Let’s say that you have a start-up and you need to reach a critical milestone within a tight deadline before being able to attract (more) investors. In order to so, you are looking to hire a new employee. Who would you hire?

- Maria, 35 years old, recently married

- Mario, 35 years old, recently married

- Simone, 35 years old, two small children, partner is employed full time

- Simon, 35 years old, two small children, partner is employed full time

Now let’s assume that they all have the same level of experience, are equally qualified and are looking for employment in Switzerland. Maria and Mario are recently married (to their respective spouses) and, given their age, it is likely that they are thinking about soon starting a family. For Mario this would mean two weeks of paid absence (thanks to changes introduced in September 2019)[i] and for Maria 14 weeks[ii]. Additionally, if Maria has complications during the pregnancy, she might have to take sick leave. Taking into account that you are on a very tight deadline (and budget), would you choose to run the risk of having your new employee being absent for at least three months? Would you hire Maria or Mario?

Let’s look at the second case. Simone and Simon both have two small children and their respective partners work full time, which means that there is no stay-at-home parent. Statistically speaking, who is more likely to have to take care of the children when they have a problem at school or when they fall ill? This is a rhetorical question in Switzerland, where there has been very little change in the traditional model of a family, in which the man works and the woman stays at home and takes care of the children (and the house). Even though the employment rate for women in Switzerland is relatively high (80% as of 2018/2019), 76% of women work only part time, even if that is not what they would like to do.[iii] A big part of this is likely to be explained by the fact that women (across the world) perform more than three-quarters of the total amount of unpaid care work (caregiving, domestic activities and community activities), giving the men relatively more time to focus on their career.[iv] Considering these facts and the values of Swiss society, and taking into account that small children often fall ill, have to be picked up from the nursery or school between 4 and 5pm every day and have around 12 weeks of holidays per year,[v] would you choose to hire the mother Simone or the father Simon? Who is more likely to have more time constraints? Who is more likely to be unable to travel?

What I am trying to highlight with this reflection is that most employers would naturally discriminate on the basis of gender because women have a naturally higher risk of ‘seasonally’ lower productivity or availability. This is particularly relevant in countries where the state offers little support for childcare, and in particular for the financing of childcare facilities (crèches). In Switzerland, one full-time place in a city crèche in 2019 costs around CHF/US$2,500 (£1950) per month, per child.[vi] Whereas gross childcare fees represent 27% of the average country salary in OECD countries, in Switzerland this value reaches 70% (for two children).[vii] Crystal has two kids, which means that the majority of her salary goes into childcare costs. Luckily, she earns more than the average salary and so does her husband. For people with a lower wage, however, childcare costs of this type would be unaffordable, so women simply stop working.

[i] OFAS (Office fédéral des assurances sociales) (18 February 2020), ‘Congé de paternité’, available at www.bsv.admin.ch/bsv/fr/home/assurances-sociales/eo-msv/reformen-und-revisionen/eo-vaterschaftsurlaub.html.

[ii] Ch.ch, ‘Maternity leave’ (no date), available at www.ch.ch/en/maternity-leave.

[iii] FSO, ‘Travail à temps partiel’ (4 March 2019), available at www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/fr/home/statistiques/situation-economique-sociale-population/egalite-femmes-hommes/activite-professionnelle/travail-temps-partiel.html.

[iv] Aleksynska et al., Working conditions in a global perspective.

[v] Expatica, ‘Education in Switzerland’ (5 November 2019), available at www.expatica.com/ch/education/children-education/education-in-switzerland-100021.

[vi] Chantal Britt, ‘No win situation: Counting the cost of childcare’, Swissinfo.ch (4 June 2013), available at www.swissinfo.ch/eng/no-win-situation_counting-the-cost-of-childcare/36026662.

[vii] OECD, ‘PF3.4: Childcare support’ (27 August 2017), available at www.oecd.org/els/soc/PF3_4_Childcare_support.pdf.

Book available worldwide on amazon.

In Switzerland, it is also possible to buy the book directly from the Author.

Dealing with rejection

Extract from Chapter 11: The personal struggles of being unemployed

From: Making Sense of My Unemployment (M.G. Ramirez-Ocando)

Self-confidence should not be dependent on external recognition, but it is hard not to doubt one’s own skills and value when others repeatedly fail to see them

The most heavily affected emotional dimension during unemployment is self-confidence. When I asked Robert, Rose and Crystal what was the hardest part of their unemployment, they all answered that it was the continued lowering of their self-esteem. Even though they were all highly educated smart professionals with many accomplishments in their lives, they all started to doubt themselves when the refusals started to pile up. Self-confidence should not be dependent on external recognition, but it is hard not to doubt one’s own skills and value when others repeatedly fail to see them. The impact on self-confidence is more obvious in some people than in others, but nobody is immune to it. The longer the unemployment, the more difficult it becomes to hide it.

For me, the hardest blows to my self-esteem happened when I was rejected for jobs after I had reached the final stage of the recruitment process. Getting to that stage almost always meant that I had spent many hours not only reading information about the company and its products (including presentations and business cases), but also preparing the best way to pitch myself for that particular company and position. This last element comprised preparing my answers to the questions most likely to be asked, which in many cases also meant preparing them in English, my second language, then translating them into a third language (German or French) in order to make sure that my limitations in that third language did not hinder the value of my answers. Getting to the last stage also meant that I had put a lot of thought into how my life would be if I got the job: would I have to move to a different city or country? Would I have to get a room where I could live during the week? Would I still be able to fly to see my parents at Christmas? Would I have the flexibility to care for my parents if an accident occurred back home? Would I need to learn to negotiate in German, French or Swiss German in a short time? What I mean to say is that it took a lot of energy to go through full recruitment processes, and by the time I got to the final interview I had already developed a very personal attachment to and an intense desire for the position. There were so many times when I came out of an interview feeling that all had gone really well and that my chances of getting the job were very good. There were so many times when I had a naïve certainty that I was going to get it. And there are so many times when I was wrong.

The most mentally and spiritually demanding part of the process is waiting for the ‘decision call’. I would check on my phone every five minutes to see if I had had an automatic rejection email or a missed call. I would be tense, anxious and unable to really focus on anything. When I got no feedback by the promised time, I would start to get angry and aggressive. The truth is that in most cases, not getting the ‘decision call’ on time meant that the company had chosen somebody else and that they were waiting for this person to accept the offer before calling the other candidates – before calling me. This period of time between the point when the company was supposed to call and the point when I was actually told the negative outcome was extremely frustrating and painful. The combination of really wanting something and knowing that it was very unlikely that I would get it, but that I still had to wait to find out, was very unhealthy. A lot of people tried to convince me to stay positive during this time, but I knew that positivity would only make the rejection more significant. Honestly, I am convinced that the best approach is to be neither positive nor negative, but simply in acceptance of not having the control over the decision.

When the time finally came and I formally received the negative outcome, I was devasted. I was not really used to failing before this unemployment experience, so I tried to see my first rejections as a learning process. But after a certain point I started to ask myself: how many failures does this learning process take? I used to tell my friends: ‘Qué es otra raya para el tigre?’ (What is another stripe for the tiger?), but actually that metaphor assumes that the tiger (me) gets its stripes through some sort of harmless colouring process. In reality these stripes felt like they were made with hot iron. It hurt having people telling me that I could not have something I really wanted, something that I felt I deserved and for which I had fought.

Not all rejections hurt the same. The first ones hurt a lot because they were unexpected, and they showed me that getting the job I wanted was actually not going to be as easy as everybody had told me. The rejections that came while I was in the middle or advanced stages of a recruitment process with other companies hurt less, because I could always refocus my energy on the next opportunity. The rejections that came in groups were particularly difficult, because that meant that I had not had time to apply for new opportunities and as a result I had nothing else positive to focus on.

Dealing with rejection is very hard for everyone. There is no magic formula to take that pain away. After a certain point I accepted that, and allowed myself a couple of days to ‘mourn’ before restarting my job search. I strongly believe that the best way to deal with rejection is by identifying what went wrong and what can be done better next time. This exercise alone is incredibly valuable, and it can recharge the motivation ‘tank’. This is the reason why I advocate so intensively for the need to request feedback after a rejection.

Book available worldwide on amazon.

In Switzerland, it is also possible to buy the book directly from the Author.

[Audio] Les défis de la recherche d’emploi: La langue

Extrait du chapitre 8: Les défis de la recherche d’emploi – Ne pas comprendre ou ne pas parler la langue locale

From: Making Sense of My Unemployment (M.G. Ramirez-Ocando)

Remarque: l’audio a été enregistré par une personne ayant un fort accent espagnol. Le texte intégral est disponible dans la vidéo

Book available worldwide on amazon.

In Switzerland, it is also possible to buy the book directly from the Author.